Why Did the U.S. Never Invade North Vietnam?

Containment: A terrible, no good, very bad idea that sounded great in theory?

The United States fought an ultimately futile limited war in Vietnam from 1963-1973. What if they had made the war unlimited and invaded North Vietnam? Would it have made a difference?

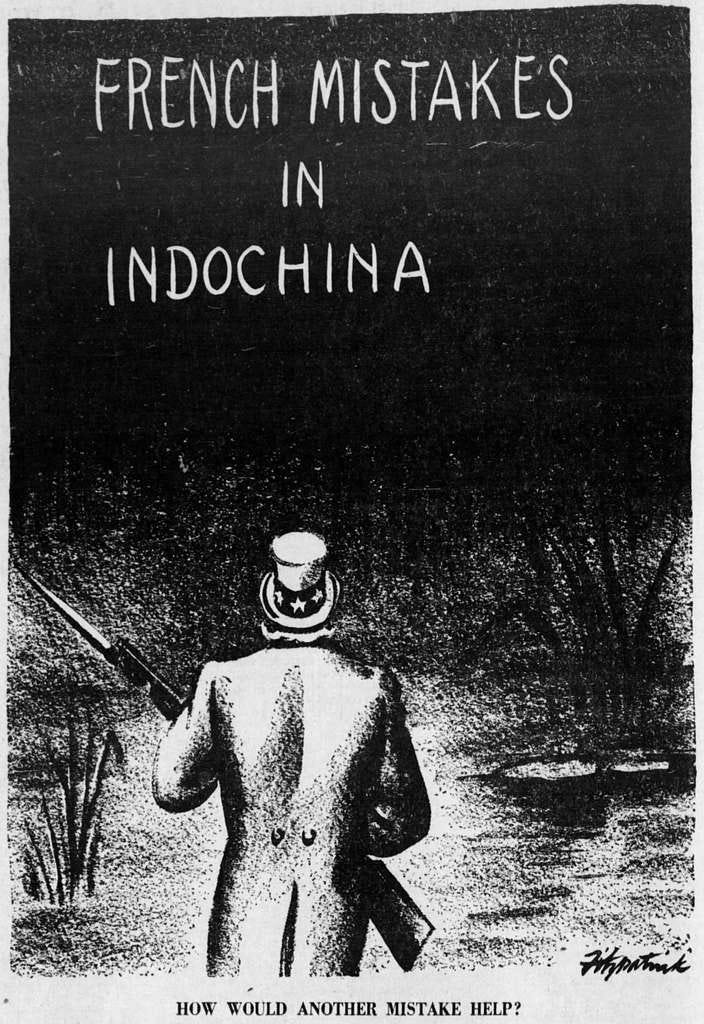

Just Another Mistake

In 1954, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a cartoon titled “French Mistakes in Indochina” with the caption, “How would another mistake help?” The cartoon was published just after the Geneva Accords ended the French War in Indochina, or the First Indochina War.

The “mistakes” are represented by a fathomless gloom. They have no beginning nor ending; they are so many that they have become something abstract. America, represented by Uncle Sam, forges into this darkness, holding his long gun.

What will Sam discover in the gloom? The cartoon leaves that up to the reader’s discretion. I’d posit: nothing at all.

Vietnam is a study in learning lessons, or the lack thereof. Many young children are taught that the oven is hot, which seems like an abstraction to them until they touch it, and realize the lesson is rooted in fact: if I touch something hot, I’ll get burned.

To me, the gloom is many things, but one of them is a hot oven. It’ll burn you, if you let it.

At the end of 1954, after the last French soldiers filed quietly out of Hanoi, taking their tricolore with them, the United States moved into their place as the policeman patrolling the Vietnamese block.

The problem was, the United States was between a hammer and anvil; a fact which became clear after the opportune time to bail had passed.

The “hammer” was an intractable collection of guerrillas called the Viet Minh. What began as a tiny meeting of Marxist theorists in the mountains of Vietnam, where a wizened Ho Chi Minh educated his cadres on the benefit of shitting far away from their food, coalesced into a revolutionary movement that threatened, and ultimately succeeded, in throwing off the French yoke.

Famously, Ho Chi Minh said the Vietnamese were like an elephant and the west (or whoever opposed them) were like a tiger. The tiger would leap out of the brush and take great swipes of flesh off with its claws, but the elephant would outlast the tiger, and inevitably crush it.

During the French Indochina War, they’d morphed from a truly pitiful lot, to a formidable force, due in part to Soviet and Chinese resources that culminated in a general counter offensive the west thought impossible.

Cadres moved 70mm guns up onto mountain heights, in some cases sacrificing their bodies underneath the guns’ wheels to prevent them sliding into a ravine.

They mobilized the people’s will into a singular focus: Dien Bien Phu.

Enter, the “anvil”: China and Soviet Russia.

In a post-Korean war world, atomic fright was ubiquitous. A new boogeyman gained traction in the halls of power in Washington: a potential evil called The Domino Theory; a concept that dictated all communist powers operated with a hive mind directed by Moscow, and it was just a matter of time until all Southeast Asia came under their heel.

That was the theory, anyway.

This situation required a great deal of tact from Washington. They couldn’t provoke the Soviets and Chinese into war, for fear of a nuclear fallout. But they also couldn’t let the communist North Vietnamese take over democratic South Vietnam and trigger the falling dominoes either.

The Post Dispatch lent their thoughts to this tenuous situation as well, “This is a war to stay out of…The intervention would commit the United States to a limited war that could only be won by making it unlimited.”1

An educated observer might pose the prescient question nobody at the time seemed to think important: “If you can’t decisively win a conflict against the North Vietnamese for fear of the Chinese and Soviets, and the South Vietnamese government is on unstable footing at best, why bother throwing your lot in with them at all?”

Barbara Tuchman in her book, March of Folly, responds:

“The answer was that self-hypnosis had worked: mixed with a vague sense of yellow peril advancing with hordes of now-Communist Chinese, there was felt to be something peculiarly sinister about Communism in Asia. As its agent, North Vietnam remained the enemy.”2

The Offensive

In November, NVA (North Vietnamese Army) troops clashed with U.S. forces in the Ia Drang valley. After ten days of bitter fighting, the Vietnamese troops were forced to retreat.

Colonel Harry Summers writes that this was the opportune time for the U.S. to mount a counter-offensive, “Although in theory the best route to victory would have been a strategic offensive against North Vietnam, such action was not in line with US strategic policy which called for containment rather than the destruction of communist power.”3

So, what is containment?

In short, it's the U.S. solution to their hammer-and-anvil conundrum. If you can’t mount a traditional offensive, but you can’t leave, either, a way forward nobody would fault is to constrict your enemy to the point that he decides he’s had enough and gives up.

In other words, Historian Edwin Moise writes:

“The idea of sending ground troops north of the 17th parallel was brought up, but never pushed really hard. Most people doubted, for good reason, that this would definitively end the conflict.”

Or, as a note delivered to the Canadian Embassy on August 8, 1964 by Washington for transmission to J. Blair Seaborn, Canadian member of the International Control Commission (ICE) says:

“RE basic American position: Mr Seaborn should again stress that US policy is simply that North Vietnam should contain itself and its ambitions within the territory allocated to its administration by the 1954 Geneva Agreements. He should stress that US policy in South Vietnam is to preserve the integrity of that state’s territory against guerrilla subversion.

“He should reiterate that the US does not seek military bases in the area and that the US is not seeking to overthrow the Communist regime in Hanoi.”4

I’m no military expert, but I imagine it’s incredibly difficult to contain a military force using the methods Moise describes. And, ultimately this proved impossible, as the Vietnamese Communists were able to establish an artery of supply through Laos with the help of the Chinese that sustained their guerrilla arm (Viet Cong) throughout the Vietnam War.

Edwin Moise brought up a nettle worth grasping, though. Sending troops north of the DMZ in an offensive against Hanoi was talked about, but never actually done. Why?

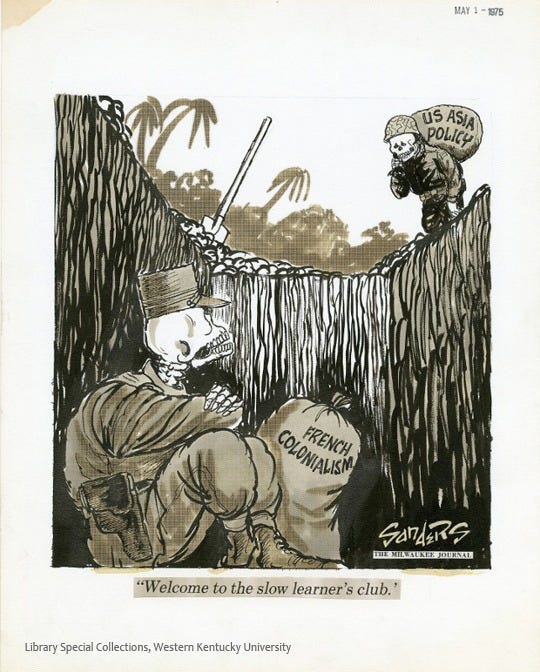

Because the French did just that in 1947.

And it didn’t work.

The French Connection

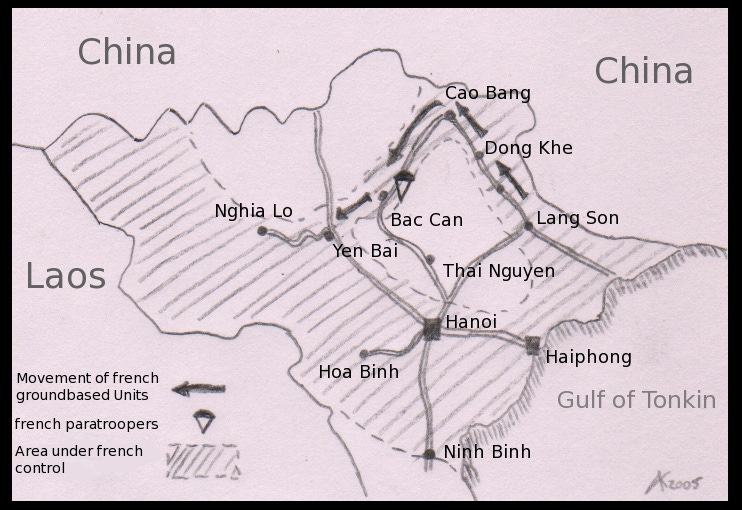

The French commander leading the 1947 fall offensive, Jean Valluy, aimed to crush the Viet Minh resistance with an all-or-nothing operation. His objective was to decapitate the movement by eliminating the Viet Minh government and killing Ho Chi Minh and General Vo Nguyen Giap.

The Viet Minh were headquartered at Viet Bac, a mountainous region north of Hanoi. Valluy told Paris that with Operation Lea, he could destroy a sizeable chunk of the Viet Minh army, isolate the Viet Minh and cut off their trading routes to southern China, and win the war in a single stroke.5

According to Frederik Logevall, the Operation was a near success. But because paratroopers took too long getting in place, it was ultimately a failure:6 “Though the DRV intelligence network had gotten wind of the operation two days earlier, a communication snafu meant that the information reached Bac Kan (Viet Bac) just as the French were launching the attack. Ho and Giap managed to get away, but with only minutes to spare. They were forced to leave behind arms and munition caches as well as stacks of secret documents.”

Operation Lea managed to kill 9,000 enemy combatants–or so the propaganda machine claimed. But, the operation critically failed to achieve any of it’s three objectives. The Viet Minh were happy to engage as much as was necessary, and when the fighting took a downward turn, Giap directed his units to slip away, content to fight another day.

Rubicon

The issue, at its core, is an issue of boundaries. The United States were afraid to push them. While the demilitarized zone (DMZ) was a very real no-fire zone and invisible fence, it was also a demarcation line in the vein of Caesar’s Rubicon. To cross it with combat troops, conventional wisdom dictated, would risk an emphatic response from the Soviets and Chinese.

ARVN (South Vietnamese) Colonel Hoan Ngoc Lung writes about the U.S. strategy, “The Americans had designed a purely defensive strategy for Vietnam. It was a strategy that was based on the attrition of the enemy through a prolonged defense and made no allowance for decisive offensive action”7

This defensive strategy is the rub of all rubs when it comes to dissecting decisions made during the Vietnam war. From the start, Rather than a ground offensive, hawks like Curtis LeMay encouraged sustained bombing north of the DMZ instead of ground forces.

While bombing is clearly an attack, it seems (from my non-expert perspective) that there’s a vague difference between sustained bombing and deploying ground forces. Bombing is abstract, even though the targets are very real, and the damage stark. But bombing is very different than an enemy annexing territory with ground forces.

I don’t exactly know where the line of demarcation between the two lies (is there an appreciable difference in cause and effect?) but clearly, decision-makers in Washington were hesitant to ruin credibility by sending forces above the DMZ, even though the North Vietnamese had cadres below the DMZ as soon as 1954, when ink on the Geneva Accords hadn’t yet dried.

Nevertheless, Washington opted for a sustained bombing of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia between 1965 and 1975 that dropped 7.6 million tons of bombs and accounted for a substantial part of the reported 2 million civilian8 casualties in the conflict.9

Harry Summers, in his book On Strategy, paints the picture of Vietnam strategy using the military theorist Clausewitz as his model: “The North Vietnamese were on the tactical defensive as part of a strategic offensive to conquer South Vietnam. Our adoption of the strategic defensive was an end in itself and we had substituted the negative aim of isolation of the battlefield. This was the fatal flaw. As Clausewitz said, ‘A major victory can only be obtained by positive measures aimed at a decision, never by simply waiting on events. in short, even in the defense, a major stake alone can bring a major gain.’ The North Vietnamese had a major stake–the conquest of Indochina. It was the United States that was ‘simply waiting on events.”10

Ultimately, the western power in the Vietnam war decided to operate in a decidedly non-western way, considering decisiveness is the spine of western warfare going back to Alexander the Great.

But, that evokes the alternative: If the U.S. grasped the initiative and invaded North Vietnam, would China and Soviet Russia have pressed their crimson buttons, plunging the world into World War Three?

If the 17th parallel was America’s Rubicon, why not cross it?

Perhaps for fear of a Sino-Soviet dagger in the back?

If you found this fascinating, there’s a good chance you’ll enjoy my podcast series about the first and second Indochina wars: Hell in a Small Place.

Tuchman, Barbara W. The March of Folly. Random House, 20 July 2011. p. 288.

Tuchman, Barbara W. The March of Folly. Random House, 20 July 2011. p. 296.

Summers, Harry G. On Strategy : A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. Novato, Ca, Presidio Press, 1982. p. 87.

Gold, Gerald, and Neil Sheehan. The Pentagon Papers. Toronto Bantam Books, 1971. p. 289.

Fredrik Logevall. Embers of War : The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam. New York, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013. p. 202.

Fredrik Logevall. Embers of War : The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam. New York, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013. p. 202.

Colonel Hoang Ngoc Lung, Strategy and Tactics (Washington, D.C.; U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1980), p. 71.

Spector, Ronald H. “Vietnam War.” Britannica, Britannica, 14 Nov. 2018, www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War.

Mark Clodfelter, The Limits of Air Power: The American Bombing of North Vietnam, Macmillan, 1989

Summers, Harry G. On Strategy : A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. Novato, Ca, Presidio Press, 1982. p. 121.